After a long time (thanks to the hack of IST), I'm returning to writing my blog. During the forced pause, I was reading a lot. Some of the books were about the decay of civilization. Here, I describe Secular cycles and The great wave.

Every nation and every civilization goes through a cycle of growth and decay. And both books try to understand these broader patterns of history.

Secular Cycles

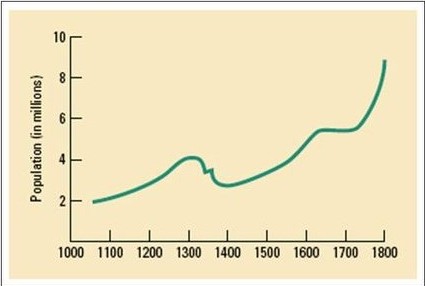

This brilliant book is about demography. It shows how the size of the population determines the proportion between rents and wages. In turn, these proportions influence the wealth distribution between elites (the ones who have the land) and workers (the ones who work for wages). The wealth distribution determines social cohesion (having a civil war or not). And everything above creates history.

One secular cycle takes around 200 years. There are four stages: expansion, stagflation, crisis, and depression.

Expansion

The cycle starts with a small population. Not everyone survived the previous one. There are few workers. They can demand higher wages. The demand for food and farmland is low. That means the rents are low.

At this time, life is good for ordinary people. They can easily support themselves and have a lot of children. Rich have land, but they cannot demand high rent for it, so the aristocracy works (as opposed to living on passive income).

Life is good on all metrics. There are no tensions in society. As an average person, you would like to live in this period. Food is available, and oppression is minimal. There is no war, except maybe some war of expansion against weaker neighbours. But the stability sows the seeds of its defeat. As the population increases, the economy changes.

Stagflation

In this phase, the population peaks or at least grows more slowly. There are a lot of people. That means a different market. Thanks to the competition, wages are down. Rents are up, and food is more expensive.

Life gets a lot tougher for ordinary people. Landowners are getting richer from rent, the wealth inequality increases. The competition to become a nobility is fiercer. And even among the rich, the wealth consolidates.

On the other hand, these are the golden years of the nation. We see big projects: wars, cathedrals, and castles. War is more common: aggressive as well as defensive. In a bad year, there can be hunger but nothing serious.

Life for ordinary people is harder (still better than in crisis). Aristocrats are getting richer and can do whatever they want. Some enjoy arts, and some fight for power. Nobody cares for the poor. In the countryside, even marginal land is farmed. Urbanization is increasing. It's impossible to earn money in the countryside. The system is under stress.

Crisis

Eventually, hunger is more common, as well as banditry. At some point, the system snaps. Some events that would be only minor problems in good times wreck everything. A few bad years increase food prices and cause famine. Or a plague (that would be just minor in times plenty) sweeps through the malnourished population. Wars and societal breakdowns always accompany these problems. No matter the initial reason in history books, the result is always the same. A lot of people die.

The crisis usually makes everything less safe. Bandits cruise the countryside, and the trade plummets. Farms become less productive without equipment and security. That means less food. Living in cities is more expensive. Usually, a revolution (or war) starts.

Depression

Life sucks for some time. Population decreases and cities get smaller. There are times when dynasty changes or the country is invaded.

Finally, after some time, a new order emerges. Someone wins the (civil) war and restores a rule of law. People start trusting each other again.

The Great wave

This book deals with a similar topic as secular cycles. It looks at them through the lenses of money and prices. The book analyses inflation and money supply.

The main price fluctuations correspond to the population. When there are many people, labour is cheap and food expensive. But in history, money was also expressed by silver or gold. It creates additional irregularities in the cycles.

Our times

The data from the past speak clearly. Cycles are there, from the roman republic to industrializing England. The question is how they translate to the current times.

The situation is different for us compared to medieval times. Only a tiny fraction of the people work in agriculture, so there is no fallback option (going back to the village). Moreover, it seems we as a world are much more food secure and spend a lot less for food than in the past.

So, developed countries can sustain a large population by importing food. There is also no ceiling for the number of jobs people can do. The work depends more on innovations now.

On the other hand, we see the cycle in front of our eyes. After the second world war, we saw population growth. Moreover, women entered the workforce. The number of workers steadily increased. It made wages grow more slowly than rents or food prices. Also, the food is still cheap, but modern life requires more than just one room for a family. Living expenses are higher because we have higher standards.

Now, the after the workforce growth, we are in a position where inequality increases significantly, and society is much less cohesive. In developed countries, the population increases only because of migration. It seems we are in a time of stagflation.

Observations

I didn't know how the population fluctuated. We have sustained population growth for almost 200 years. Nobody remembers anything different. We don't know what happens to the economy when the population decreases and deurbanizes. Land and housing are much less valuable. Returns on investment are much lower.

In this world, we can lose a good outlook on the future, stop investing and then live in a world where nothing is better than it was before. We would expect deflation, and it would come. These times came in the past a few times already.

On the bright side, we also see that humanity is resilient. There were almost world-ending catastrophes: wars, famines, and pestilence. Multiple times roughly 30% of the population died, but eventually, we recovered. Some catastrophes were even necessary to get where we are now.

It is hard to say if life will be better in hundred years, but in 250 years, it will be better. So hopefully see you then.